Reevaluating an overlooked 1971 soul classic

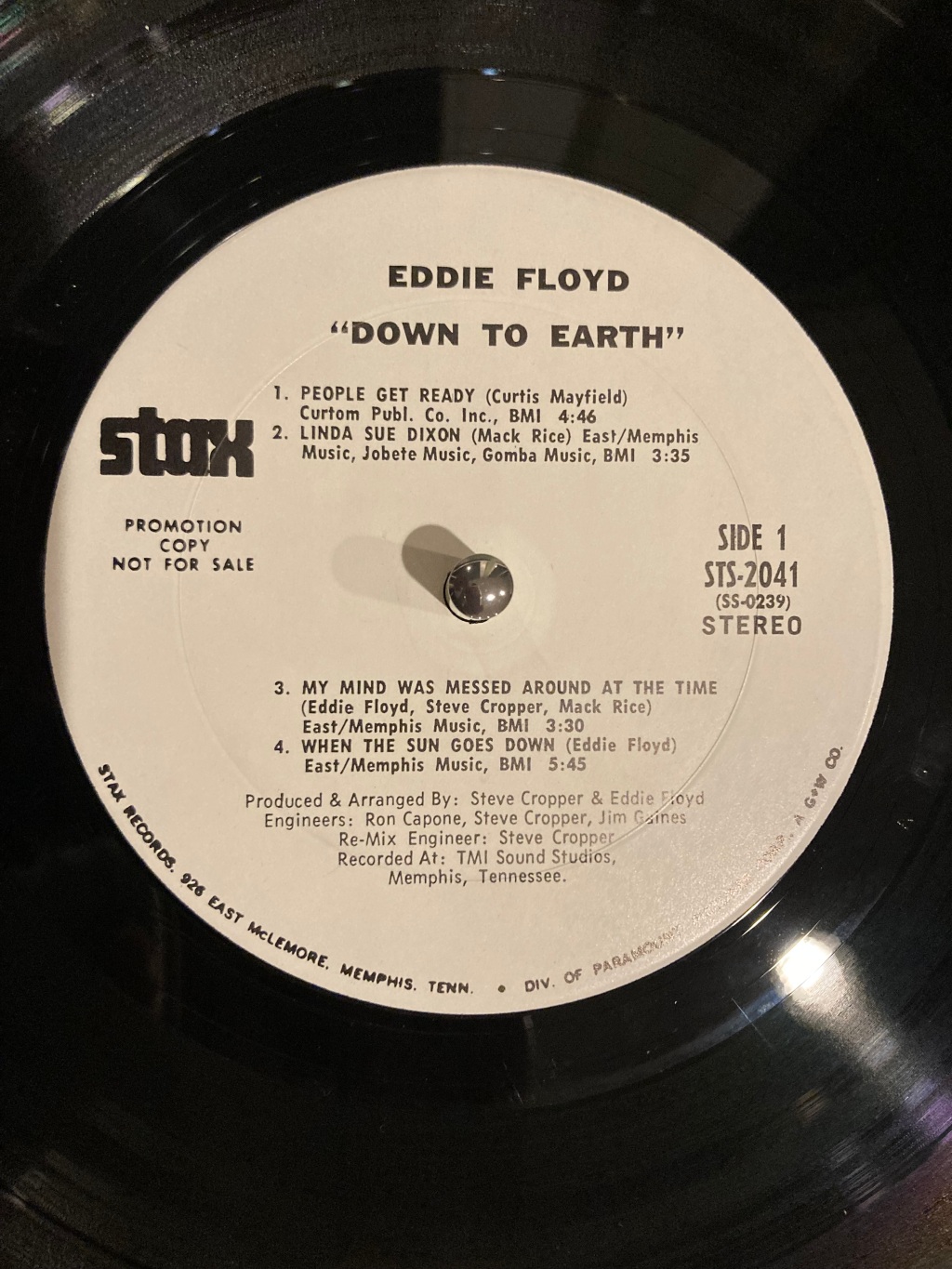

In 1971, two of soul music’s most important musicians coproduced one of the genre’s wildest albums. Despite its unassuming title, on Down to Earth singer-songwriter Eddie Floyd and guitarist-songwriter Steve Cropper took soul music to new frontiers.

But let’s back up. I had no idea that’s what I was getting myself into when I purchased a copy of Down to Earth well over a decade ago from Rochester’s Record Archive. On the surface, there was little to suggest that the record would be a departure from other R&B of the same vintage. Floyd smiles pleasantly from the cover, crouching in a denim-on-denim outfit that looks positively restrained compared to some of the outrageously vibrant suits that his former band-mate Wilson Pickett had been wearing on album covers for years. And the record was released on Stax, the iconic label that is the epitome of the classic brand of southern soul known as the “Memphis sound.” By 1971, Floyd and Cropper had both spent years at Stax releasing music that defined the sound of soul music. Fans of the genre know Floyd for a string of classic hits including Knock on Wood (cowritten with Cropper), Raise Your Hand, I’ve Never Found a Girl, and California Girl. Likewise, everyone has heard Cropper whether they know it or not—it’s his eloquent guitar on Sam & Dave’s anthemic Soul Man, Otis Redding’s immortal Dock of the Bay (which he co-wrote), the ubiquitous Green Onions, and countless others.

But within seconds of dropping the needle I learned that Floyd and Cropper had something different in mind for Down to Earth. The album begins with a screaming electric guitar fanfare that seems to announce, “your attention please, we’re trying something new here.” The tempo slows. The first song is a cover of the social consciousness ballad People Get Ready by Curtis Mayfield & The Impressions. “People get ready, there’s a train a-coming” Floyd sings with appropriate deference for the original. In fact, for a few measures the arrangement is routine enough that a listener might think that they imagined the phrenetic opening. But then the band again hits the gas. The slow rolling freedom train of Mayfield’s original is transformed into a speeding locomotive powered by driving guitar and pounding piano. Sonically, it sounds as much like a protype for the Who’s gritty 5:15 as it does one of Floyd’s 60s soul hits. The album rarely lets up in intensity or creativity from there.

Another fascinating track is the cover of the euphemistic Linda Sue Dixon (“Your name might be Linda Sue Dixon, to some folks baby . . . you’re plain old LSD to me now”). Written by Sir Mack Rice (more on this later), the song was previously recorded with some success by the Detroit Wheels. Apart from the thinly-veiled drug reference, the Down to Earth version is remarkable for its marriage of Stax soul, aggressive drumming, and, of all things, down-home fiddle. The combination once again recalls the Who, specifically their 1971 hit Baba O’Riley which features a similar instrumental palate. Fiddle makes for a peculiar sonic addition to the standard soul instrumentation, but the fusion seems appropriate coming from Stax, which was originally co-founded by Jim Stewart, himself a fiddle player.

Equally intriguing is Salvation, which ventures into prog/southern rock territory with blistering guitar and keyboards that sound like they would be at home on an Allman Brothers record later in the decade (Jessica comes to mind). The strangest song on Down to Earth may be the six-and-a-half minute Changing Love, a funky brew that at various points includes buzzed out electric guitar, bongos, and an interlude where Floyd moans “oh baby” through an echo effect over a sparse drum and keyboard backing.

In the midst of all the innovation, Floyd and Cropper reached back nearly 40 years with one song selection, the 1934 standard I Only Have Eyes for You, perhaps best known for its seminal 1959 doowop reading by the Flamingos. Floyd and Cropper give the track a 70s soul facelift with smooth backing vocals and polished horns. But the ghost of the Flamingos version is still lurking beneath the surface—a nice reminder of the influence of doo-wop and R&B vocal groups on soul music and of Floyd’s time in his own vocal group, the Falcons with Wilson Pickett and Sir Mack Rice (the aforementioned composer of Linda Sue Dixon, as well as Mustang Sally and Respect Yourself, and a background singer on Down to Earth).

Down to Earth features a wealth of gripping material, but perhaps the greatest highlight is the idiosyncratic When the Sun Goes Down. Over the course of six minutes and several tempo shifts, the song synthesizes old and new into a soul masterpiece. The song begins with bluesy acoustic guitar and Floyd moaning, “I, oh, I, oh yeah, now, I want to tell you about my baby.” Floyd follows it with a vocal swoop that sounds like an earthier version of Jackie Wilson, and then the band and horns come in with a slow ballad accompaniment of the sort Stax had perfected as early as Otis Redding’s 1962 single These Arms of Mine. There’s another brief acoustic interlude and then a loud call and response between Floyd and a crunchy electric guitar. That transitions into a bluesy horn-driven roadhouse shuffle that sounds like it could have been a lost B.B. King track as Floyd implores, “I just want to be loved.” By the end, the song shifts to a groove somewhere between a Creedence Clearwater Revival choogle and a John Lee Hooker boogie.

So how did Floyd and Cropper come to record an album that sounds so unlike anything else in the Stax catalog? The liner notes don’t offer any explanation, because like many soul albums of the 60s and 70s there basically aren’t any.

One factor may have been that the Stax of 1971 was a much different record label than the Stax of the early-to-mid sixties. 1968 marks a dividing line of sorts in the history of Stax. The tragic death of Otis Redding and several members of the Bar-Kays in a December, 1967 plane crash meant that Stax began 1968 without its biggest star and several key session musicians. Further compounding this incalculable human and artistic loss, Stax would end 1968 without the rights to its entire back catalog of foundational soul hits due to a business miscalculation. As author Robert Gordon details in Respect Yourself, his excellent history of the label, Stax relied on a distribution deal with the larger Atlantic records to alchemize its recordings into national hits. Gordon writes that when Stax pulled out of that contract in 1968 it learned that it “owned nothing.” Apart from a royalty, Atlantic maintained the ownership of all the masters for music it distributed for Stax. That began a mad dash by Stax executives to create a new catalog from scratch—an ambitious endeavor called the Soul Explosion, which resulted in some musical experiments that pushed the Stax sound beyond the boundaries of its pre-1968 era. Down to Earth came three years into the new era of Stax records. Although Stax was still releasing straight-ahead southern soul, by 1971 many of the label’s releases had become far more ambitious in scope—featuring complex string arrangements and interesting effects. For an illustration, just listen to Isaac Hayes’ 12-minute recording of Walk On By from his 1969 album Hot Buttered Soul or the Booker T. & the M.G.s’ album McLemore Avenue from 1970 (a fascinating reworking of the Beatles’ Abbey Road).

Down to Earth’s marriage of soul singing and instrumentation with rock guitar and psychedelia may also be less surprising against the backdrop of broader musical trends. Before 1971 a number of R&B artists had incorporated aspects of psychedelia into their material. In the 1968 song Let’s Get an Understanding, Wilson Pickett remarks “hey Bobby, I think you’re all drifting over to a psychedelic bag” after a trippy guitar solo. The next year, Peggy Scott & Jo Jo Benson had a hit with the song Soulshake, which featured electric sitar. By 1970 the Temptations had named an entire album Psychedelic Shack (after the 1969 single contained on the album). Rock more generally was a frequent part of the sonic palate of R&B by 1971. Check out Duane Allman’s guitar parts on Aretha Franklin’s 1970 cover of The Weight and Pickett’s 1969 version of Hey Jude. Speaking of Pickett, perhaps the best proof of the extent to which rock had found its way into the R&B terrain is his 1969 cover of Steppenwolf’s Born to Be Wild.

But of course much of the innovation is attributable to the artistic vision of Floyd and Cropper. In his autobiography Time is Tight, Booker T. Jones (organ visionary of Booker T. & the MG’s and countless Stax productions) described Floyd as having a “natural affinity for creativity”—a searcher willing to try new things. Those attributes are readily apparent throughout Down to Earth, and Cropper and Floyd clearly must have fed off each other’s ideas.

Admittedly, Down to Earth is not the place to start a soul music collection, or even a Stax collection for that matter. Not every idea worked, some aspects of the arrangements feel dated, and the frequent tempo shifts can make the album a turbulent listening experience. But Down to Earth is an excellent record on its own terms and is deservedly starting to get some overdue attention. Fans of the genre, the label, or the period should find it a rewarding and fascinating release for several reasons. For one thing, Floyd really gets to stretch out with his singing. His phrasing on the album is a master class in soul. Second, Cropper had a genius for giving songs exactly what they needed and nothing more—innovative guitar licks and fills that elevated hits with perfect hooks. But that role sometimes kept him confined. On Down to Earth, Cropper gets a chance to shred, and it provides an opportunity to hear his guitar hero technique unleashed. But perhaps the greatest treat in listening to Down to Earth is in pondering the road not taken. I find it impossible to listen to Down to Earth without wondering how the course of southern soul might have changed if the album had caught on.

And that takes us to where we began. When I was inspecting the copy of Down to Earth that I purchased all those years ago, there actually was one sign that it might be something out of the ordinary. It was a white label promo copy—the sort that record labels gave to DJs and promoters to try and turn new material into hits. But the copy looked un-played.

Non-algorithmic final thoughts:

Anyone wanting another soul-rock hybrid should take a listen to the 2007 album The Scene of the Crime by Bettye LaVette, featuring the Drive-By Truckers. The gritty mix of LaVette’s soulful vocals and the loud guitars of the Truckers feels like a logical continuation of the sounds pioneered on Down to Earth and in recordings like Pickett’s Born to Be Wild. Guitar buffs interested in hearing another album where Cropper gets plenty of time in the limelight should check out Jammed Together, a 1969 jam session-turned album featuring three of Stax’s most important guitarists: Cropper, Pops Staples, and Albert King. Anyone looking for a starting point to get into Eddie Floyd or Stax may want to track down a copy of the Complete Stax-Volt Singles 1959-1968, a great 9 CD box set that can be found used at reasonable prices. Finally, I highly recommend Respect Yourself by Robert Parker for a truly gripping history of Stax and the musicians and figures who built it.

Leave a comment